In autumn 2018, Community Links decided to start a weekly emergency food support service from our base in Canning Town. We took this decision because a number of people coming to our services told us they were hungry, and that they didn’t have enough food to feed themselves and their children. Our service users are not alone: in 2018/19, the Trussell Trust reported a 19% increase in foodbank usage since the previous year and gave out 1.6 million food parcels, one third of which fed children.

Once we decided to start an emergency food support service, we mapped out existing provision in the area. We found that four foodbanks existed within a 45-minute walk of Community Links, though only one was open full-time, and all had specific criteria for referrals. To reduce some of the barriers to people in Canning Town accessing food, we began our own weekly support service on Wednesday evenings – a day when no other service in the immediate area was providing food. Furthermore, we decided we would not have any referral criteria for people accessing the service.

Getting started

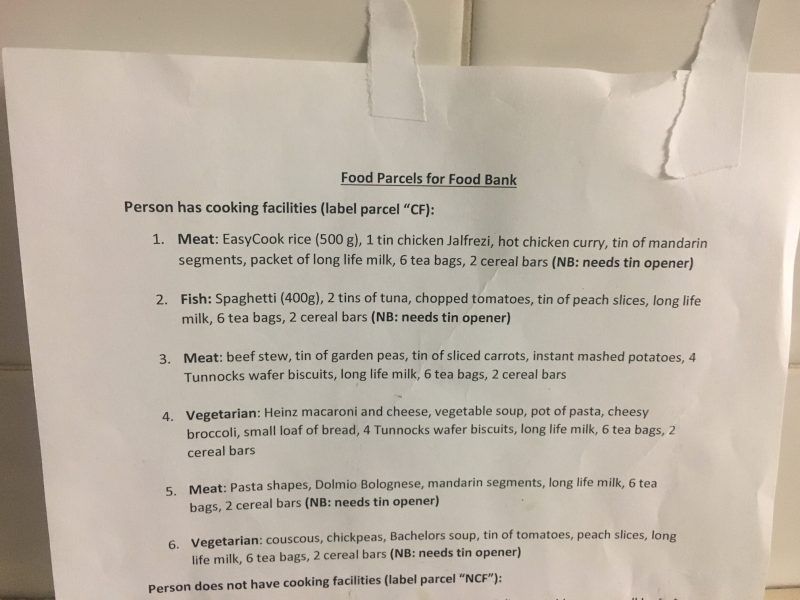

We made a list of contents for eight different parcels, making sure that we had vegetarian and halal options as well as parcels that were suitable for people with no cooking facilities beyond a kettle or microwave. In addition to tinned food, each parcel included long-life milk, tea, bread and cereal bars.

Because Community Links is based in a former town hall, we are fortunate to have plenty of room to host services. We would ask people to sit and have a cup of tea or coffee while we completed a seven-question survey with them about what had led them to need a food parcel. Each Wednesday session would be run by three Community Links staff. We would pay for the food ourselves for the first six months, then decide if there was a need for the service. If so, we would try to make the emergency food service sustainable through donations.

We opted not to advertise our service in the first instance. Newham is a tight-knit community, so we expected word of mouth to spread the news about our food service. We put a simple sign outside our door and opened in mid-September.

Opening the doors

The first evening, only one person showed up. This gentleman had been in the UK for several years and was still waiting for the outcome of his immigration case. He was not legally allowed to work but had taken jobs that paid in cash to support his wife and children. Over a cup of tea, he told us this was the first time he had been unable to provide food for them. He felt ashamed that he had to use our service. Going forward, we would find that many people who came to our emergency food support service felt this way. We worked hard to create a positive environment so they would not feel this way.

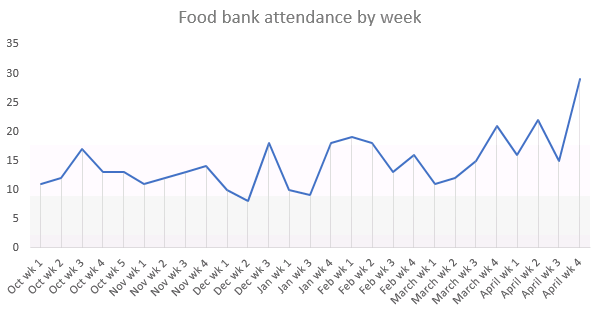

The second week, we had a significant uptick to 12 people; clearly, word had spread as we expected. We continued to average about this many people for the rest of 2018. Many people came every week, with only one or two new people coming in each week. In late January 2019, we therefore decided to advertise in a few local places to attract other people who might need our support. We put small signs up in two local grocery stores and a few local schools. A few weeks after this, more people started coming. By the end of our six-month pilot, we were seeing between 20 and 25 people each week, a significant increase from when we started. In the first six months, we provided 450 food parcels, which fed 619 adults and 209 children.

The graph below shows the attendance levels at the emergency food support service in its first six months. Beyond the general increase in clients from October to April, it also suggests a specific pattern of use. The spikes mostly happen during weeks 3 and 4 of each month, suggesting that people struggle to make their income (whether from work or benefits) last until the end of the month. This insight is supported by some of our testimony, in which people told us that they could make their income last for the first two weeks but could not afford to buy food by the end of the month.

Reasons for attendance

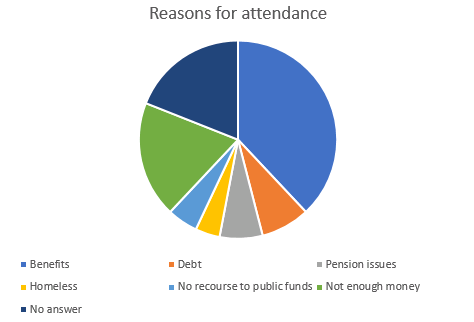

We asked each person who attended the emergency food support service to tell us why they needed a food parcel. Some people did not want to go into detail about their circumstances, saying simply “I’m hungry” or “Don’t have enough money”. Others told us about the multiple problems they faced that had led them to need a food parcel.

Benefits problems were cited as the leading reason that people needed a food parcel: 38% of attendees said this was their main issue. This covers a wide range of issues, including:

- not having enough benefits income to cover basic costs

- waiting for benefits (in particular Universal Credit) to be paid

- paying back benefits overpayments

- dealing with sanctions/suspension of benefits

- waiting on appeals for benefits such as Employment Support Allowance.

- Debt, pension issues, homelessness, and immigration issues (with No Recourse to Public Funds) were also cited as reasons people needed food parcels.

Furthermore, 12% of people who attended the service said they had a physical or mental illness that aggravated their financial issues and contributed to their need for food support. The pie chart below shows the breakdown of common reasons people attended the service.

My mum is on Employment and Support Allowance and we are not able to cover the cost of food due to other costs on travel, and my dad doesn’t work.

11 year old boy filling out the form for his mother, who did not speak fluent English

I have been looking for work and my benefits have been cut. I don’t have enough money to feed my family.

Male, aged 40-44

I’m clearing rent arrears, so I don’t have much left for food. I can usually manage off my Employment and Support Allowance but it’s very tight.

Female, aged 50-54

We have used this qualitative and quantitative data in our research on the effects of Universal Credit, including the five-week waiting period. We have responded to local and national government consultations about the welfare system and debt. We have also added our voice to several campaigns based on our findings, including:

- The Trussell Trust’s #5WeeksTooLong campaign to end the five week wait on Universal Credit

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s #EndTheFreeze campaign to end the benefits freeze early.

- Refugee Action’s #LiftTheBan campaign to allow asylum seekers to find employment.

Supporting the whole person, not just the problem

One of Community Links’ founding principles is that of Deep Value relationships, the value created when the human relationships between people delivering and people using public services are effective. We believe it is the deeper qualities of the human bond that nourish confidence, inspire self-esteem, unlock potential, erode inequality and so have the power to transform. We designed our emergency food support service along these lines.

As mentioned, each client was offered a cup of tea or coffee and engaged in a conversation about underlying problems that had led them to need a food parcel. Community Links staff explained to clients what services were available at Community Links (debt advice, welfare benefits advice, digital skills classes etc). If a client was interested, staff took their mobile number and a brief description of the problem, and they were contacted by relevant staff and given an appointment. Similarly, Community Links staff were encouraged to refer their clients to the emergency food service if they thought it would be helpful.

As a result of this holistic way of working, we found that 31% of emergency food support clients received other kinds of assistance from Community Links. Most people attended one of our advice services, but other signed up for our employability programmes. Several also attended Catch22’s employment service, which is based in Community Links’ building. We found that 88% of people who sought help from other Community Links or Catch22 services did not need to attend the emergency food support service on a long-term basis.

Case studies

It is important to note the complexity of problems that lead people to need food support. While some people’s problems can be fixed quickly, others need longer-term support despite their best efforts to help themselves. Selina* (not her real name) shared her story with us, demonstrating how complicated people’s situations can be.

Selina* moved to the UK in 1986 from outside the European Union and worked in a school cafeteria. She is in now in her early 60s. Two years ago, her leave to remain was revoked due to a bureaucratic error. As a result, her benefits were suspended and she was no longer allowed to work. She had to hire a solicitor to help her resolve the issue. To pay for this and her daily expenditure, she took out a loan from a private company. She was also in arrears on her Council Tax and the Council was requesting payment. Because her housing benefit had been stopped, she was being threatened with eviction. She first came to Community Links for help stopping the eviction, and while here was referred to the emergency food support service.

At the beginning of 2019, the immigration issue was resolved and Selina was able to apply for Universal Credit. Due to low digital skills and a learning disability, she could not do this on her own (Universal Credit is a “digital by default” service, meaning that it is administered entirely online).

Selina told us this:

At first they said I should go to the job centre and someone will help me. When I went there, they said they can’t help me and put me on the computer to do things. And I said I can’t do it and told them I will come to Community Links to see if someone can help me.

A Community Links advisor helped her apply for Universal Credit. She then waited another five weeks to receive her first payment, as has been standard for Universal Credit. During this time she had no money except a small loan from the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP), and relied on the emergency food support to have enough to eat. Furthermore, DWP has notified her that they overpaid her Job Seekers’ Allowance by nearly £500 in 2017 and will take this money out of her Universal Credit payments.

Selina continues to attend our emergency food support service because her payments minus her mandatory repayments are not sufficient to cover her living costs. She has enrolled in a digital skills course at Community Links but continues to need help updating her Universal Credit journal online. Selina is also getting help from a career advisor but due to her proximity to pension age she is struggling to find a job.

Next steps

We have now reached the end of our six-month pilot. It has demonstrated that there is a clear need for an emergency food support service in Canning Town. Our aim is to make this service sustainable in the next few months.

We have started to work with our corporate partners and have received an enthusiastic response from them in terms of both food and volunteers. We would like to keep this going, but take it further. We would like to do additional fundraising for food and an adviser who would link the advice team with the emergency food support service. This would allow us to become sustainable while also ensuring that people receive the holistic support that they need to move forward.